This guideline purports to offer comprehensively stipulated specifications to CN/EN subtitling, referntial sources include literature reviews, BBC Guidelines, Netflix partnership documents, personal notes and captioning group specifications. Adherence to iron rules and selective conformity to trivia are suggested for optimised effects.

PDF版本:下载

Subtitling Specification and Guidelines

(Heading-navigation available)

Collated by BDZzzz

Last revision on 27th Sep. 2023

General Groundings (As stipulated by the BBC)

Prefer verbatim

If there is time for verbatim speech, do not edit unnecessarily. Your aim should be to give the viewer as much access to the soundtrack as you possibly can within the constraints of time, space, shot changes, and on-screen visuals, etc. You should never deprive the viewer of words/sounds when there is time to include them and where there is no conflict with the visual information.

However, if you have a very “busy” scene, full of action and disconnected conversations, it might be confusing if you subtitle fragments of speech here and there, rather than allowing the viewer to watch what is going on.

Don’t automatically edit out words like “but”, “so” or “too”. They may be short but they are often essential for expressing meaning.

Similarly, conversational phrases like “you know”, “well”, “actually” often add flavour to the text.

Do not simplify

It is not necessary to simplify or translate for deaf or hard-of-hearing viewers. This is not only condescending, but also frustrating for lip-readers.

Retain speaker’s first and last words

If the speaker is in shot, try to retain the start and end of their speech, as these are most obvious to lip-readers who will feel cheated if these words are removed.

Edit evenly

Do not take the easy way out by simply removing an entire sentence. Sometimes this will be appropriate, but normally you should aim to edit out a bit of every sentence.

Keep names

Avoid editing out names when they are used to address people. They are often easy targets, but can be essential for following the plot.

Preserve the style

Your editing should be faithful to the speaker’s style of speech, taking into account register, nationality, era, etc. This will affect your choice of vocabulary. For instance:

Similarly, make sure if you edit by using contractions that they are appropriate to the context and register. In a formal context, where a speaker would not use contractions, you should not use them either.

Regional styles must also be considered: e.g., it will not always be appropriate to edit “I’ve got a cat” to “I’ve a cat”; and “I used to go there” cannot necessarily be edited to “I’d go there.”

Consistency

KNPs/formality tables must be created and used for translation to ensure consistency across episodes and seasons.

Keep the form of the verb

Avoid editing by changing the form of a verb. This sometimes works, but more often than not the change of tense produces a nonsense sentence. Also, if you do edit the tense, you have to make it consistent throughout the rest of the text.

Keep words that can be easily lip-read

Sometimes speakers can be clearly lip-read - particularly in close-ups. Do not edit out words that can be clearly lip-read. This makes the viewer feel cheated. If editing is unavoidable, then try to edit by using words that have similar lip-movements. Also, keep as close as possible to the original word order.

Subtitle illegible text

If the onscreen graphics are not easily legible because of the streamed image size or quality, the subtitles must include any text contained within those graphics which provide contextual information. This must include the speaker’s identity, what they do and any organisations they represent. Other displayed information affected by legibility problems that must be included in the subtitle includes; phone numbers, email addresses, postal addresses, website URLs, or other contact information.

If the information contained within the graphics is off-topic from what is being spoken, then the information should not be replicated in the subtitle.

Main titles/dedications

Subtitle the main title as instructed in the timed text style guide of the respective language

Subtitle all plot-pertinent and otherwise relevant on-screen text that is not covered in dialogue and/or redundant in the target language such as: “Based on True Events”, “In Loving Memory of Jane”, etc.

Quotation Translations

It is best practice to originate new translations for any quoted texts, as this allows for a translation free of rights issues. In cases of a compelling artistic or cultural reason to use an existing translation, they may be used only if:

Translator credits

Please include the translator credit as the last event of the subtitle file, using the approved translation provided in the Original Credits translation document.

If more than one translator has worked on an asset, e.g., when translating from multiple source languages or when more than one translator has collaborated on a special project, more than one translator can be mentioned in the same credit, as follows:

Subtitle translation by:

Will Byers, Jane Hopper

Specific Formatting Rules

Fonts

Font style: Arial (SimHei for Chinese) as a generic placeholder for proportionalSansSerif.

Font size: Relative to video resolution and ability to fit 42 characters across screen.

Font colour: White.

Positioning

All subtitles should be centre justified and placed at either the top or bottom of the screen, except for Japanese, where vertical positioning is allowed.

For 16:9 video in landscape mode, subtitles should not be placed outside the central 90% vertically and the central 75% horizontally. Regions can be extended horizontally to allow extra space for line padding.

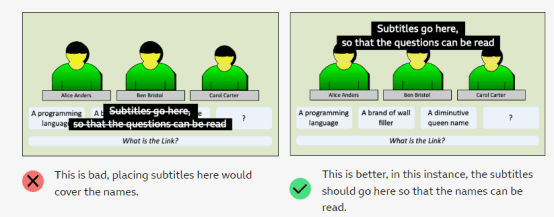

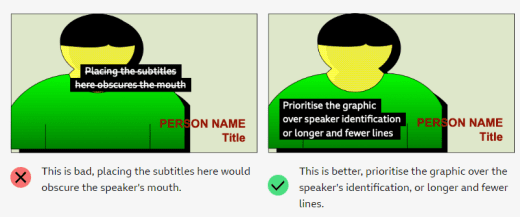

Please ensure subtitles are positioned accordingly to avoid overlap with onscreen text. In cases where overlap is impossible to avoid (text at the top and bottom of the screen), the subtitle should be placed where easier to read.

e.g., Vertical positioning:

Horizontal positioning:

Numbers

From 1 to 10, numbers should be written out: one, two, three, etc. (see below exceptions)

Above 10, numbers should be written numerically: 11, 12, 13, etc. (see below exceptions)

When a number between 0 and 99 begins a sentence, it should always be spelled out. Numbers over 100 which start a sentence can be written numerically.

Ensure consistency in sequences which feature numbers and counting.

When writing percentages, always write in numerals and use the % symbol.

For long sequences of numbers, e.g., phone numbers or social security numbers, always use numerals and follow the spacing and formatting appropriate to the region.

Always use numerals when writing units of measurement

Always write out ordinal numbers as words when not used in reference to dates, e.g., “They came first in the race”, “This is the second time I have told you”. Write ordinal numbers numerically when in reference to date, e.g., “1st March” or when they need to be replicated in an FN for on-screen text.

Times of day:

Special Circumstances:

It takes 1kJ of energy to lift someone.

It takes one kJ of energy to lift someone.

She gave me hundreds of reasons

She gave me 100s of reasons

Three days from now.

3 days from now.

On her 21st birthday party, 54 guests turned up

the score was three - 1

There are 1,500 cats here.

Dates and decades

Dates should always be written in the order in which they are said (i.e. as per the audio) but omitting words like “the” and “of”, i.e. 6th March or March 6th, not the 6th of March.

Decades should be written using numerals in the following format: nineteen fifties should be 1950s, fifties should be ‘50s.

Centuries should be written in the following format: twentieth century should be 20th century.

Do not use ‘50s, ‘70s etc. for ages: i.e., prefer “I am in my fifties” vs. “I am in my ‘50s” or “I am in my 50s”.

Currency

Currency should not be converted in the subtitle files. Any mention of money amounts in dialogue should remain in the original currency.

Strong language

Do not edit out strong language unless it is absolutely impossible to edit elsewhere in the sentence - deaf or hard-of-hearing viewers find this extremely irritating and condescending.

Bleeped words

If the offending word is bleeped, put the word BLEEP in the appropriate place in the subtitle - in caps, in a contrasting colour and without an exclamation mark.

BLEEP

If only the middle section of a word is bleeped, do not change colour mid-word:

f-BLEEP-ing

Dubbed words

If the word is dubbed with a euphemistic replacement - e.g., frigging - put this in. If the word is non-standard but spellable put this in, too:

frerlking

If the word is dubbed with an unrecognisable sequence of noises, leave them out.

Muted words

If the sound is dipped for a portion of the word, put up the sounds that you can hear and three dots for the dipped bit:

Keep your f...ing nose out of it!.

Never use more than three dots.

If the word is mouthed, use a label:

So (MOUTHS) f...ing what?

Titles

Brand Names Treatment

Treatment can be handled in one of the following ways:

Do not swap one brand for another company’s trademarked item.

The available techniques include:

Colour: This is the preferred method that should be used in most cases.

Single quotes: Used to indicate an out-of-vision speaker, such as someone speaking via telephone, or to distinguish between in- and out-of-vision voices when both are spoken by the same character (or by the narrator) and therefore using the same colour (e.g., a narrator who is sometimes in-vision).

Arrows: Used to indicate the direction of out-of-vision sounds when the origin of the sound is not apparent. (infrequently used)

Label: Can be used to resolve ambiguity as to who is speaking.

Horizontal positioning: This is a legacy technique for identifying in-vision speakers, but it is still used for indicating off-screen speech. It is also used with Vertical positioning to avoid obscuring important information.

Dashes: This is a legacy technique. Must only be used with colour when unavoidable.

Use colours

Use colours to distinguish speakers from each other. This is the preferred method for identifying speakers.

Where the speech for two or more speakers of different colours is combined in one subtitle, their speech runs on: i.e., you don’t start a new line for each new speaker.

Did you see Jane? I thought she went home.

However, if two or more WHITE text speakers are interacting, you have to start a new line for each new speaker, preceded by a dash.

By convention, the narrator is indicated by a yellow colour.

Use horizontal positioning

This is a legacy technique that is no longer used in new content for identifying in-vision speakers (it may be present in files created before it was deprecated). Use colour instead.

Horizontal positioning is used in combination with arrows to indicate out-of-vision voices.

Put each piece of speech on a separate line or lines and place it underneath the relevant speaker. You may have to edit more to ensure that the lines are short enough to look placed.

Try to make sure that pieces of speech placed right and left are “joined at the hip” if possible, so that the eye does not have to leap from one side of the screen to the other.

Not:

![]()

When characters move about while speaking, the caption should be positioned at the discretion of the subtitler to identify the position of the speaker as clearly as possible.

Use hyphens (Netflix, recommended)

Use a hyphen without a space to indicate two speakers in one subtitle, with a maximum of one speaker per line.

-Are you coming?

-In a minute.

When identifiers are needed, they should follow the hyphen as follows:

-[Kimmy] Are you coming?

-[Titus] In a minute.

-[Kimmy] Are you coming?

-In a minute.

Hyphens are also used to indicate a speaker and a sound effect, if they come from different sources:

-[Joe laughing hysterically]

-[Maria] I can’t believe you did that!

-[Joe laughing hysterically]

-I can’t believe you did that!

If the sound effect emanates from the speaker themselves, no hyphens are needed:

[Joe laughing hysterically]

I can’t believe you did that!

Use hyphens to distinguish two distinct sound effects emanating from different sources:

-[horse neighs]

-[engine starts]

Text in each line in a dual speaker subtitle must be a contained sentence and should not carry into the preceding or subsequent subtitle. Creating shorter sentences and timing appropriately helps to accommodate this.

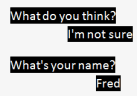

Use single quotes for voice-over

If you need to distinguish between an in-vision speaker and a voice-over speaker, use single quotes for the voice-over, but only when there is likely to be confusion without them (single quotes are not normally necessary for a narrator, for example). Confusion is most likely to arise when the in-vision speaker and the voice-over speaker are the same person.

Put a single quote-mark at the beginning of each new subtitle (or segment, in live), but do not close the single quotes at the end of each subtitle/segment - only close them when the person has finished speaking, as is the case with paragraphs in a book.

‘I’ve lived in the Lake District since I was a boy.

‘I never want to leave this area.

I’ve been very happy here.

‘I love the fresh air and the beautiful scenery.’

If more than one speaker in the same subtitle is a voice-over, just put single quotes at the beginning and end of the subtitle.

‘What do you think about it? I’m not sure.’

The single quotes will be in the same colour as the adjoining text.

Use single quotes for out-of-vision speaker

When two white text speakers are having a telephone conversation, you will need to distinguish the speakers. Using single quotes placed around the speech of the out-of-vision speaker is the recommended approach. They should be used throughout the conversation, whenever one of the speakers is out of vision.

Hello. Victor Meldrew speaking.

‘Hello, Mr Meldrew. I’m calling about your car.’

Single quotes are not necessary in telephone conversations if the out-of-vision speaker has a colour.

Use double quotes for mechanical speech and for quoting

Double quotes “...” can suggest mechanically reproduced speech, e.g., radio, loudspeakers etc., or a quotation from a person or book. Start the quote with a capital letter:

He said, “You’re so tall”.

Use arrows for off-screen voices (Usually in live captioning only)

Generally, colours should be used to identify speakers. However, when an out-of-shot speaker needs to be distinguished from an in-shot speaker of the same colour, or when the source of off-screen/off-camera speech is not obvious from the visible context, insert a ‘greater than’ (>) or ‘less than’ (<) symbols to indicate the off-camera speaker.

If the out-of-shot speaker is on the left or right, type a left or right arrow (< or >) next to their speech and place the speech to the appropriate side. Left arrows go immediately before the speech, followed by one space; right arrows immediately after the speech, preceded by one space.

Do come in.

Are you sure? >

When are you leaving?

< I was thinking of going

at around 8 o’clock in the evening.

When I find out where he is,

you’ll be the first to know. >

NOT:

When I find out where he is, >

you’ll be the first to know.

If possible, make the arrow clearly visible by keeping it clear of any other lines of text, i.e., the text following the arrow and the text in any lines below it are aligned. However, not all formats support hanging indent well.

Non-breaking spaces can be inserted to simulate the indent behaviour reasonably closely.

< When I find out where he is,

you’ll be the first to know

The arrows are always typed in white regardless of the text colour of the speaker.

If an off-screen speaker is neither to the right nor the left, but straight ahead, do not use an arrow.

Arrow characters (← and →) can be used instead of < and > for online-only subtitles.

Use labels for off-screen voices

If you are unable to use any other technique, use a label to identify a speaker, but only if it is unclear who was speaking or when more than four characters are speaking, requiring a shared colour. Type the name of the speaker in white caps (regardless of the colour of the speaker’s text), immediately before the relevant speech.

If there is time, place the speech on the line below the label, so that the label is as separate as possible from the speech. If this is not possible, put the label on the same line as the speech, centred in the usual way.

JAMES:

What are you doing with that hammer?

JAMES: What are you doing?

If you do not know the name of the speaker, indicate the gender or age of the speaker if this is necessary for the viewer’s understanding:

MAN: I was brought up in a close-knit family.

When two or more people are speaking simultaneously, do the following, regardless of their colours:

Two people:

BOTH: Keep quiet! (all white text)

Three or more:

ALL: Hello! (all white text)

TOGETHER: Yes! No! (different colours with a white label)

Repetitions

Do not subtitle words or phrases repeated more than once by the same speaker unless the repetition is plot-pertinent

If the repeated word or phrase is said twice in a row, time subtitle to the audio but translate only once.

Punctuation (Cf. Illocutionary Forces and Perlocutionary Effects)

English

不使用的标点

每行行中不保留逗号,不使用分号

行尾不保留句号 句中句号也用一个空格代替

一般不使用冒号,用空格代替

例外:表示时间时,如 10:30,使用英文半角冒号

常用标点

强调,特殊含义,引用时使用

引用他人言论时,前引号前的冒号或者逗号应删去

若引用的语句超过一轴,需在每轴保留一对双引号

话未说完,或者表示意犹未尽时使用

比较少用的标点:

列举事物时,使用顿号

添加说明时使用

使用英文括号,左括号左边、右括号右边各加一空格,与正文隔开 【例外:数学算式如 f(x) 不需要加空格】

必要时可使用

表示书籍时,英文字幕中的双引号,改为中文书名号

并在书名号内括号注明英文书名

Italics

Italicize text only in the following cases:

Italics may be used when a word is obviously emphasized in speech and when proper punctuation cannot convey that emphasis (e.g., It was).

In trailers, where dialogue rapidly switches between off-screen characters, on-screen characters and narrators, do not italicize any dialogue from the characters and speakers and only italicize narration.

Avoid going back and forth between italicized and non-italicized subtitles when the speaker is on and off screen. If the speaker is on-camera for at least part of the scene, do not italicize. Leave italics for off-screen narrators.

This is the only set of rules to be followed for application of italics and trumps any additional advice found in associated references.

He told me, “Come back tomorrow.”

He said, “‘Singing in the Rain’ is my favorite song.”

Subtitle 1 “Good night, good night!”

Subtitle 2 “Parting is such sweet sorrow

Subtitle 3 that I shall say good night till it be morrow.”

Periods and commas precede closing quotation marks, whether double or single.

Colons and semicolons follow closing quotation marks.

Which of Shakespeare’s characters said, “Good night, good night”?

Juliet said, “Good night, good night!”

Foreign Dialogues

In instances of foreign dialogue being spoken:

Foreign words that are used in a mostly English line of dialogue do not require identifiers, but should be italicized. Always verify spelling, accents and punctuation, if applicable.

Familiar foreign words and phrases which are listed in Webster’s dictionary should not be italicized and should be spelled as in Webster’s dictionary (e.g., bon appétit, rendezvous, doppelgänger, zeitgeist, etc.).

Proper names, such as foreign locations or company names, should not be italicized.

Always use accents and diacritics in names and proper nouns from languages which use the Latin alphabet where their use is seen in official sources, or in the source text for fictional names. For example, Spanish names such as Mónica Naranjo, Pedro Almodóvar, Plácido Domingo should retain their diacritics. Any proper names which have lost the use of accents due to cultural reasons (e.g., Jennifer Lopez) do not need to have them added.

Transliterate uncommon or unfamiliar letters/characters which appear in names or proper nouns when working from a Roman alphabet language into English if they may cause confusion or be hard to understand or pronounce. Note that diacritics should be kept in proper nouns and names. For example: If the Icelandic name Þór appears, please transliterate as Thór (following relevant KNP and guidance about handling character names). If a German street name such as Torstraße appears in the source, please transliterate as Torstrasse (following relevant KNP and guidance about handling character names).

Naming Translation

Chinese

English

Do not translate proper names unless your project provides approved translations.

Nicknames should only be translated if they convey a specific meaning.

Use language-specific translations for historical/mythical characters (e.g., Santa Claus).

When translating Korean, Simplified Chinese and Traditional Chinese content, the name order should be last name-first name, in accordance with linguistic rules. For South Korean names, first name should be connected with a hyphen, with second letter in lower case (i.e., 김희선: Kim Hee-sun), and North Korean names, first name is written without a hyphen (i.e. Kim Jong Un). For Chinese names, first name should be connected without a space, with only the first letter in upper case (i.e., 宁世征: Ning Shizheng). When Romanizing names into English, standardized romanization guides should be followed, but well-established localized names should be allowed as exceptions.

Music and songs

Music formatting (Netflix, recommended)

[“Forever Your Girl” playing].

[“The Nutcracker Suite” plays].

Follow this approach for poetry but do not include music notes.

Label source music

All music that is part of the action, or significant to the plot, must be indicated in some way. If it is part of the action, e.g., somebody playing an instrument/a record playing/music on a jukebox or radio, then write the label in upper case:

SHE WHISTLES A JOLLY TUNE

POP MUSIC ON RADIO

MILITARY BAND PLAYS SWEDISH NATIONAL ANTHEM

Describe incidental music

If the music is “incidental music” (i.e., not part of the action) and well known or identifiable in some way, the label begins “MUSIC:” followed by the name of the music (music titles should be fully researched). “MUSIC” is in caps (to indicate a label), but the words following it are in upper and lower case, as these labels are often fairly long and a large amount of text in upper case is hard to read.

MUSIC: “The Dance Of The Sugar Plum Fairy”

by Tchaikovsky

MUSIC: “God Save The Queen”

MUSIC: A waltz by Victor Herbert

MUSIC: The Swedish National Anthem

(The Swedish National Anthem does not have quotation marks around it as it is not the official title of the music.)

Combine source and incidental music

Sometimes a combination of these two styles will be appropriate:

HE HUMS “God Save The Queen”

SHE WHISTLES “The Dance Of The Sugar Plum Fairy”

by Tchaikovsky

Label mood music only when required

If the music is “incidental music” but is an unknown piece, written purely to add atmosphere or dramatic effect, do not label it. However, if the music is not part of the action but is crucial for the viewer’s understanding of the plot, a sound-effect label should be used:

EERIE MUSIC

Indicate song lyrics with #

Song lyrics are almost always subtitled - whether they are part of the action or not. Every song subtitle starts with a white hash mark (#) and the final song subtitle has a hash mark at the start and the end:

# These foolish things remind me of you #

There are two exceptions:

In cases where you consider the visual information on the screen to be more important than the song lyrics, leave the screen free of subtitles.

Where snippets of a song are interspersed with any kind of speech, and it would be confusing to subtitle both the lyrics and the speech, it is better to put up a music label and to leave the lyrics unsubtitled.

For online content, instead of # the symbol, ♫ may be used.

Avoid editing lyrics

Song lyrics should generally be verbatim, particularly in the case of well-known songs (such as God Save The Queen), which should never be edited. This means that the timing of song lyric subtitles will not always follow the conventional timings for speech subtitles, and the subtitles may sometimes be considerably faster.

If, however, you are subtitling an unknown song, specially written for the content and containing lyrics that are essential to the plot or humour of the piece, there are a number of options:

edit the lyrics to give viewers more time to read them

combine song-lines wherever possible

do a mixture of both - edit and combine song-lines.

NB: If you do have to edit, make sure that you leave any rhymes intact.

Synchronise with audio

Song lyric subtitles should be kept closely in sync with the soundtrack. For instance, if it takes 15 seconds to sing one line of a hymn, your subtitle should be on the screen for 15 seconds.

Song subtitles should also reflect as closely as possible the rhythm and pace of a performance, particularly when this is the focus of the editorial proposition. This will mean that the subtitles could be much faster or slower than the conventional timings.

There will be times where the focus of the content will be on the lyrics of the song rather than on its rhythm - for example, a humorous song like Ernie by Benny Hill. In such cases, give the reader time to read the lyrics by combining song-lines wherever possible. If the song is unknown, you could also edit the lyrics, but famous songs like Ernie must not be edited.

Where shots are not timed to song-lines, you should either take the subtitle to the end of the shot (if it’s only a few frames away) or end the subtitle before the end of the shot (if it’s 12 frames or more away).

Centre lyrics subtitles

All song-lines should be centred on the screen.

Punctuation

It is generally simpler to keep punctuation in songs to a minimum, with punctuation only within lines (when it is grammatically necessary) and not at the end of lines (except for question marks). You should, though, avoid full stops in the middle of otherwise unpunctuated lines. For example,

Turn to wisdom. Turn to joy

There’s no wisdom to destroy

Could be changed to:

# Turn to wisdom, turn to joy

There’s no wisdom to destroy

In formal songs, however, e.g., opera and hymns, where it could be easier to determine the correct punctuation, it is more appropriate to punctuate throughout.

The last song subtitle should end with a full stop, unless the song continues in the background.

If the subtitles for a song don’t start from its first line, show this by using two continuation dots at the beginning:

# ..Now I need a place to hide away

# Oh, I believe in yesterday. #

Similarly, if the song subtitles do not finish at the end of the song, put three dots at the end of the line to show that the song continues in the background or is interrupted:

# I hear words I never heard in the Bible... #

Sound effects

Subtitle effects only when necessary

As well as dialogue, all editorially significant sound effects must be subtitled. This does not mean that every single creak and gurgle must be covered - only those which are crucial for the viewer’s understanding of the events on screen, or which may be needed to convey flavour or atmosphere, or enable them to progress in gameplay, as well as those which are not obvious from the action. A dog barking in one scene could be entirely trivial; in another it could be a vital clue to the story-line. Similarly, if a man is clearly sobbing or laughing, or if an audience is clearly clapping, do not label.

Do not put up a sound-effect label for something that can be subtitled. For instance, if you can hear what John is saying, JOHN SHOUTS ORDERS would not be necessary.

Describe sounds, not actions

Sound-effect labels are not stage directions. They describe sounds, not actions:

GUNFIRE

not:

THEY SHOOT EACH OTHER

Netflix sound effect formats (recommended, Cf. Specific Formatting Rules – Speaker Identifiers – Use hyphens)

Subtitle 1: However, lately, I’ve been…

[coughs, sniffs]

Subtitle 2: …seeing a lot more of this.

[narrator] Once upon a time, there was…

BBC sound effect formats (legacy)

A sound effect should be typed in white caps. It should sit on a separate line and be placed to the left of the screen - unless the sound source is obviously to the right, in which case place to the right.

There is no style attribute that enforces all caps; the text needs to be capitalised within the subtitle document.

Subject + verb

Sound-effect labels should be as brief as possible and should have the following structure: subject + active, finite verb:

FLOORBOARDS CREAK

JOHN SHOUTS ORDERS

Not:

CREAKING OF FLOORBOARDS

Or

FLOORBOARDS CREAKING

Or

ORDERS ARE SHOUTED BY JOHN

In-vision translations

If a speaker speaks in a foreign language and in-vision translation subtitles are given, use a label to indicate the language that is being spoken. This should be in white caps, ranged left above the in-vision subtitle, followed by a colon. Time the label to coincide with the timing of the first one or two in-vision subtitles. Bring it in and out with shot-changes if appropriate.

If there are a lot of in-vision subtitles, all in the same language, you only need one label at the beginning - not every time the language is spoken.

If the language spoken is difficult to identify, you can use a label saying TRANSLATION:, but only if it is not important to know which language is being spoken. If it is important to know the language, and you think the hearing viewer would be able to detect a language change, then you must find an appropriate label.

Animal noises

The way in which subtitlers convey animal noises depends on the content style. In factual wildlife, for instance, lions would be labelled:

LIONS ROAR

However, in an animation or a game, it may be more appropriate to convey animal noises phonetically. For instance, “LIONS ROAR” would become something like:

Rrrarrgghhh!

Special Instructions

Illocutionary Forces and Perlocutionary Effects

Intonation and emotion

Sarcasm

Charming(!)

You’re not going to work today, are you(?)

Stress

It’s the BOOK I want, not the paper.

I know that, but WHEN will you be finished?

HELP ME!

Whisper

WHISPERS:

Don’t let him near you.

(Don’t let him near you.)

Incredulous question

You mean you’re going to marry him?!

Accents

Indicate accent only when Required

Indicate accent sparingly

Incorrect grammar

I and my wife is being marrying four years since and are having four childs, yes

I and my wife have been married four years and have four childs, yes

Use label

AMERICAN ACCENT:

All the evidence points to a plot.

Difficult speech

Edit Lightly

Consider the dramatic effect

Use labels for incoherent speech

(SLURRED): But I love you!

Use labels for inaudible speech

APPLAUSE DROWNS SPEECH

TRAIN DROWNS HIS WORDS

MUSIC DROWNS SPEECH

HE MOUTHS

Explain pauses in speech

INTRODUCTORY MUSIC

LONG PAUSE

ROMANTIC MUSIC

Break up subtitles slow speech

Indicate stammer

I’m g-g-going home

W-W-What are you doing?

Hesitation and interruption

Indicate hesitation only if important

Within a single subtitle

Pause within a sentence

Everything that matters...is a mystery

How are you? ..Oh, I’m glad to hear that.

Unfinished sentence

Hello, Mr... Oh, sorry! I’ve forgotten your name

Unfinished question/exclamation

What do you think you’re...?!

Interruption

Across subtitles

Indicate time lapse with dots

I think...

I would like to leave now.

I’d like...

..a piece of chocolate cake

Humour

Separate punchlines

Reactions

Keep catchphrases

Cumulative subtitles

Only use when necessary

Common scenarios

Timing

Avoid cumulative where shots change

Avoid obscuring important information

Stick to three lines

Line Breaks

Line length

BBC

Max length: 68% of the width of a 16:9 video and 90% of the width of a 4:3 video.

The number of characters that generate this width is determined by the font used, the given font size (see fonts) and the width of the characters in the particular piece of text (for example, ‘lilly’ takes up less width than ‘mummy’ even though both contain the same number of characters).

Netflix

42 characters per line for most Latin alphabet languages.

Maximum for Chinese subtitles: 16 characters per line.

CEA-708 Closed Captions

For CEA-708 closed captions in 4:3 aspect ratio the screen is divided in 32 columns which also mean that there might be 32 characters at most at each text line.

For videos in 16:9, 1.85:1 or 2.39:1 aspect ratio the screen is 42 columns wide instead and 42 characters can be inserted on each text line.

Single line preference

Text should usually be kept to one line, unless it exceeds the character limitation.

Two-line threshold principle

BBC & Netflix: A maximum subtitle length of two lines is recommended. Three lines may be used if you are confident that no important picture information will be obscured. When deciding between one long line or two short ones, consider line breaks, number of words, pace of speech and the image.

Prioritise editing and timing over line breaks

Good line-breaks are extremely important because they make the process of reading and understanding far easier. However, it is not always possible to produce good line-breaks as well as well-edited text and good timing. Where these constraints are mutually exclusive, then well-edited text and timing are more important than line-breaks.

Break at natural points

Text should usually be kept to one line, unless it exceeds the character limitation.

Prefer a bottom-heavy pyramid shape for subtitles when multiple line break options present themselves, but avoid having just one or two words on the top line.

Subtitles and lines should be broken at logical points. The ideal line-break will be at a piece of punctuation like a full stop, comma or dash. If the break has to be elsewhere in the sentence, avoid splitting the following parts of speech:

However, since the dictates of space within a subtitle are more severe than between subtitles, line breaks may also take place after a verb. For example:

We are aiming to get

a better television service.

Line endings that break up a closely integrated phrase should be avoided where possible.

We are aiming to get abetter television service.

Line breaks within a word are especially disruptive to the reading process and should be avoided. Ideal formatting should therefore compromise between linguistic and geometric considerations but with priority given to linguistic considerations.

Normally, the line should be broken:

Short sentences

Short sentences may be combined into a single subtitle if the available reading time is limited. However, you should also consider the image and the action on screen. For example, consecutive subtitles may reflect better the pace of speech.

Long sentences

In most cases verbatim subtitles are preferred to edited subtitles so avoid breaking long sentences into two shorter sentences. Instead, allow a single long sentence to extend over more than one subtitle. Sentences should be segmented at natural linguistic breaks such that each subtitle forms an integrated linguistic unit. Thus, segmentation at clause boundaries is to be preferred. For example:

When I jumped on the bus

I saw the man who had taken

the basket from the old lady.

Segmentation at major phrase boundaries can also be accepted as follows:

On two minor occasions

immediately following the war,

small numbers of people

were seen crossing the border.

There is considerable evidence from the psycho-linguistic literature that normal reading is organised into word groups corresponding to syntactic clauses and phrases, and that linguistically coherent segmentation of text can significantly improve readability.

Random segmentation must certainly be avoided:

On two minor occasions

immediately following the war, small

numbers of people, etc.

In the examples given above, no markers are used to indicate that segmentation is taking place. It is also acceptable to use sequences of dots (three at the end of a to-be-continued subtitle, and two at the beginning of a continuation) to mark the fact that a segmentation is taking place, especially in legacy subtitle files.

Dual speaker subtitles (Cf. Specific Formatting Rules – Speaker identifiers)

Use a hyphen without a space to indicate two speakers in one subtitle, with a maximum of one speaker per line.

-Are you coming?

-In a minute.

Text in each line in a dual speaker subtitle must be a contained sentence and should not carry into the preceding or subsequent subtitle. Creating shorter sentences and timing appropriately helps to accommodate this.

For example:

Sub 1

-Has anybody delivered any artwork?

-I don’t think so,

Sub 2

but let me check with Irene.

Should be reformatted as:

Sub 1

Has anybody delivered any artwork?

Sub 2

I don’t think so

but let me check with Irene.

Dialogue continuity

English

Subtitle 1 I always knew

Subtitle 2 that you would eventually agree with me.

Subtitle 1 Had I known…

Subtitle 2 I wouldn’t have called you.

-What are you--

-Be quiet!

-What are you--

-[bomb explodes]

She hesitated… about accepting the job.

…have signed an agreement.

Chinese

Subtitle 1 她过来这里告诉我

Subtitle 2 她会回来

Subtitle 1 –但你说⋯

Subtitle 2 –我知道他说什么

Subtitle 1 –今天的天气很⋯

Subtitle 2 –她很漂亮

⋯很有意思

Timing

General rules on synchronisation

All instructions under the “Timing” section by default applies to 24 fps formats. Modify time specifications accordingly when dealing with different frame rates.

Subtitles should be in sync with both the image and the audio.

Subtitles should sit neatly within shots creating an effortless viewing experience which is easy on the eye.

Avoid spoilers (i.e., pre-empting an effect): always avoid revealing punchlines or major plot-points early where there is a visible reaction on screen.

It is permissible to slip out of sync when you have a sequence of subtitles for a single speaker, providing the subtitles are back in sync by the end of the sequence.

Word Rate

English:

The recommended subtitle speed is 160-180 words-per-minute (WPM) or 0.33 to 0.375 second per word. However, viewers tend to prefer verbatim subtitles, so the rate may be adjusted to match the pace of the programme.

Chinese:

Minimum and maximum timing

BBC

Based on the recommended rate of 160-180 words per minute, you should aim to leave a subtitle on screen for a minimum period of around 0.3 seconds per word (e.g., 1.2 seconds for a 4-word subtitle). However, timings are ultimately an editorial decision that depends on other considerations, such as the speed of speech, text editing and shot synchronisation. When assessing the amount of time that a subtitle needs to remain on the screen, think about much more than the number of words on the screen; this would be an unacceptably crude approach.

Netflix

Minimum duration: ⅚ (five-sixths) second per subtitle event (e.g., 20 frames for 24fps; 25 frames for 29.97fps).

Maximum duration: 7 seconds per subtitle event.

When to give less time

Do not dip below the target timing unless there is no other way of getting round a problem. Circumstances which could mean giving less reading time are:

Shot changes

Give less time if the target timing would involve clipping a shot, or crossing into an unrelated, “empty” [containing no speech] shot. However, always consider the alternative of merging with another subtitle.

Lip reading

Give less time to avoid editing out words that can be lip-read, but only in very specific circumstances: i.e., when a word or phrase can be read very clearly even by non-lip-readers, and if it would look ridiculous to take out or change the word.

Catchwords

Avoid editing out catchwords if a phrase would become unrecognisable if edited.

Retaining humour

Give less time if a joke would be destroyed by adhering to the standard timing, but only if there is no other way around the problem, such as merging or crossing a shot.

Critical information

In a news item or factual content, the main aim is to convey the “what, when, who, how, why”. If an item is already particularly concise, it may be impossible to edit it into subtitles at standard timings without losing a crucial element of the original.

Very technical items

These may be similarly hard to edit. For instance, a detailed explanation of an economic or scientific story may prove almost impossible to edit without depriving the viewer of vital information. In these situations, a subtitler should be prepared to vary the timing to convey the full meaning of the original.

When to give extra time

Try to allow extra reading time for your subtitles in the following circumstances:

Unfamiliar words

Try to give more generous timings whenever you consider that viewers might find a word or phrase extremely hard to read without more time.

Several speakers

Aim to give more time when there are several speakers in one subtitle.

Labels

Allow an extra second for labels where possible, but only if appropriate.

Visuals and graphics

When there is a lot happening in the picture, e.g., a football match or a map, allow viewers enough time both to read the subtitle and to take in the visuals.

Placed subtitles

If, for example, two speakers are placed in the same subtitle, and the person on the right speaks first, the eye has more work to do, so try to allow more time.

Long figures

Give viewers more time to read long figures (e.g., 12,353).

Shot changes

Aim for longer timing if your subtitle crosses one shot or more, as viewers will need longer to read it.

Slow speech

Slower timings should be used to keep in sync with slow speech.

Use consistent timing

It is also very important to keep your timings consistent. For instance, if you have given 3:12 for one subtitle, you must not then give 4:12 to subsequent subtitles of similar length - unless there is a very good reason: e.g., slow speaker/on-screen action.

Detailed timing specifications

Normal in-time and out-time

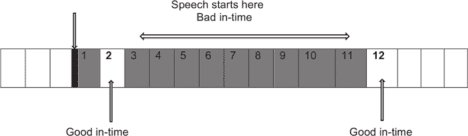

In-time

Subtitles should have an in-time which is on the first frame of audio or as close to it as possible (within 1-2 frames of the first frame of audio is acceptable), using the waveform as reference, unless the scenario falls into the timing to shot change rules).

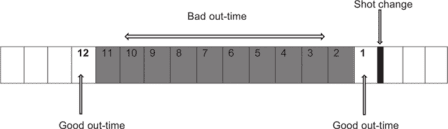

Out-time

Keep lag behind speech to a minimum.

The out-time can be extended up to half a second past the timecode at which the audio ends. (BBC: Subtitles should never appear more than 2 seconds after the words were spoken. This should be avoided by editing the previous subtitles.)

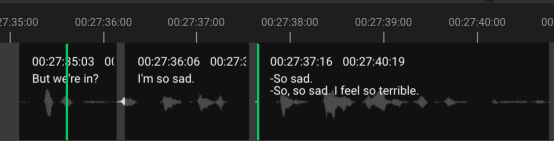

Frame gap/Anti-flicker/Chaining/Closing gaps/Avoiding jerky effects

Netflix (Recommended):

When timing a sequence of subtitles, create a run of subtitles with even gaps by bumping up the out-time of the previous subtitle to two frames (regardless of frame rates) before the in-time of the new subtitle where any gaps of fewer than half a second exist. This is sometimes known as “chaining” or “closing gaps”. This is described further below.

Do not simply conflate two consecutive subtitles together in time cueing, that will make it difficult for the viewers to discern that the line has changed, especially when lengths of the two lines are similar.

More specifically:

BBC:

If there is a pause between two pieces of speech, you may leave a gap between the subtitles - but this must be a minimum of one second, preferably a second and a half. Anything shorter than this produces a very jerky effect. Try to not squeeze gaps in if the time can be used for text.

Timing to the shot change

Simple cases

Where dialogue starts on the shot change or within half a second past the shot change, please set the in-time to the first frame of the shot change.

If an out-time is within half a second of the last frame before the shot change, extend the out-time to the shot change, respecting the two-frame gap from the shot change.

That is to say, in-times and out-times may be brought forward or extended to be in sync with shot changes within the half-second parameter in order to create an even viewing experience and to allow the subtitles to fit neatly within the edit of the content.

If dialogue ends before a shot change and there is no subtitle after the shot change, you should still set the out-time to two frames before the shot change.

These rules can be applied when the out-time has already been extended by half a second past the audio but apply good judgement when determining if a subtitle looks like it is hanging on-screen for too long and apply timing adjustments accordingly.

Merge subtitles for short shots

If one shot is too fast for a subtitle, then you can merge the speech for two shots – provided your subtitle then ends at the second shot change.

Bear in mind, however, that it will not always be appropriate to merge the speech from two shots: e.g., if it means that you are thereby “giving the game away” in some way. For example, if someone sneezes on a very short shot, it is more effective to leave the “Atchoo!” on its own with a fast timing (or to merge it with what comes afterwards) than to anticipate it by merging with the previous subtitle.

Wait for scene change to subtitle speaker

Some film techniques introduce the soundtrack for the next scene before the scene change has occurred. If possible, the subtitler should wait for the scene change before displaying the subtitle. If this is not possible, the subtitle should be clearly labelled to explain the technique.

Try to avoid straddling shot changes

Avoid creating subtitles that straddle a shot change (i.e. a subtitle that starts in the middle of shot one and ends in the middle of shot two). To do this, you may need to split a sentence at an appropriate point, or delay the start of a new sentence to coincide with the shot change.

Having to cross/straddle shot changes

Subtitles may cross shot changes when the dialogue they represent also crosses the shot change. Note that: subtitles may not cross scene changes except in cases where a character/speaker starts speaking before the shot change but the dialogue features in a subsequent scene. In these instances, ensure the italics and segmentation rules are applied correctly.

When dialogue starts before a shot change, the in-time must be at least half a second before the shot change following the time to audio rules.

To accommodate this, the in-time should either be brought forward to half a second before the shot change (e.g., when the dialogue starts 9, 10 or 11 frames before the shot change in 24 fps content), or moved up to the first frame of the new shot.

When dialogue crosses the shot change and if reading speed permits, the out-time may be adjusted to either be two frames before the shot change or at least half a second after it.

Documentary

For non-English source languages using the Latin alphabet, only the speaker’s title should be translated. Do not include the speaker’s name, company name or character name as these are redundant.

Only translate a speaker’s title once, the first time the speaker appears in the documentary.

When ongoing dialogue is interrupted by a speaker’s title, use ellipsis at the end of the sentence in the subtitle that precedes it and at the beginning of the sentence in the subtitle that follows it.

Subtitle 1 I worked on this movie…

Subtitle 2 (FN) DIRECTOR

Subtitle 3 …for a total of six months.

Dialogue in TV/movie clips should only be subtitled if plot-pertinent and if the rights have been granted.

News tickers/banners from archive clips do not require subtitles unless plot-pertinent.

Again, avoid going back and forth between italicized and non-italicized subtitles when the speaker is on and off screen in a documentary. If the speaker is on-camera for at least part of the scene, do not italicize. Leave italics for off-screen narrators.

Forced Narrative Subtitles

General groudings

A Forced Narrative (FN) subtitle is a text overlay that clarifies communications or alternate languages meant to be understood by the viewer. They can also be used to clarify dialogue, texted graphics or location/person IDs that are not otherwise covered in the dubbed/localized audio. To enable the same viewing experience across multiple countries and devices, FN subtitles are localized and delivered as separate timed ¬text files. The picture in your primary video (A/V MUX) that would otherwise have subtitles is required to be delivered as a non-subtitled file, or textless. Subtitles, both full and FN, are not burned-in over picture.

Use cases

FN subtitles are used in the following cases:

1. Short segments of foreign language, intended to be understood by the audience, that differ from the original language of the show.

Example: Subtitles set to “Off”, but FN subtitle still displays when this Warrior Nun character speaks Italian.

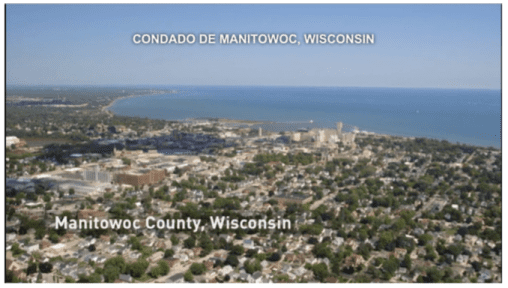

2. Translation of original language location/person IDs, dates or other labels (e.g., “White House, December 10”). As a creative element, these text graphics are usually burned into image and are therefore represented as FN’s in foreign languages only. The screenshot below illustrates a graphic location ID (Manitowoc County, Wisconsin) in English with the Spanish FN subtitle translation (Condado De Manitowoc, Wisconsin).

3. Communication that would not otherwise be commonly understood (e.g., sign language, a subtitled dog, Klingons).

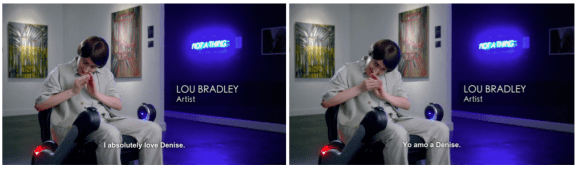

Example: English and Spanish FN subtitles are used clarify sign language. Note: In contrast to the FN text overlay, the middle third is a creative graphic element and is therefore burned into picture.

Example: English FN subtitle coverage of Klingon dialogue

4. Transcribed dialogue in the same language, often done for audience clarification (if audio is inaudible or distorted, commonly in documentaries).

Formatting

Forced narrative titles for on-screen text should only be included if plot-pertinent and as specified in the show guide (where available)

When on-screen text and dialogue overlap, precedence should be given to the most plot-pertinent message.

Avoid over truncating or severely reducing reading speed in order to include both dialogue and on-screen text

Follow the guidelines for timings of FNs for on-screen text as found in the subtitle timing guidelines

Forced narratives for on-screen text should be in ALL CAPS, except for long passages of on-screen text (e.g., prologue or epilogue), which should use sentence case to improve readability

Do not end an FN for on-screen text with a period/full stop unless the FN represents long passages of on-screen text which needs to be punctuated

Do not use italics in an FN representing on-screen text, even if a title or foreign word is present

Never combine a forced narrative with dialogue in the same subtitle or dual speaker subtitle

When a plot-pertinent forced narrative interrupts dialogue, use an ellipsis at the end of the sentence in the subtitle that precedes it and at the beginning of the sentence (without a space) in the subtitle that follows it.

Subtitle 1 I don’t think we should…

Subtitle 2 (FN) NO TRESPASSING

Subtitle 3 …go any further.

Foreign dialogues (Cf. Specific formatting rules – Foreign dialogues)

Foreign dialogue should only be titled if the viewer was meant to understand it.

Please follow the usual treatment for foreign words or phrases for the language (italics, translation, transliteration).

Unfamiliar foreign words and phrases should be italicized, if applicable for your language. A foreign dialogue exchange should not be italicized.

Timing

Forced narratives which translate on-screen text should mimic the timing of the on-screen text and be perfectly in sync. Apply these timings as far as the maximum duration and minimum duration rules permit.

To ensure synchronicity when timing in and out with on-screen text which fades in and out, aim to set the in-time and out-time halfway through the fade and watch the section back to check for sync.

If on-screen text remains on screen for the duration of a shot, you should maintain the standard rule for the out-time: fix the out-time two frames before the shot change.

These rules for timing FNs for on-screen text override advice given relating to timing to shot and audio when subtitling dialogue.

FN subtitles representing on-screen text may be brought out early where dialogue is present and takes precedence.

Children’s subtitling

The following guidelines are recommended for the subtitling of programmes targeted at children below the age of 11 years (ITC).

Editing

There should be a match between the voice and subtitles as far as possible.

A strategy should be developed where words are omitted rather than changed to reduce the length of sentences.

For example,

Can you think why they do this?

Why do they do this?

Can you think of anything you could do with all the heat produced in the incinerator?

What could you do with the heat from the incinerator?

Difficult words should also be omitted rather than changed. For example:

First thing we’re going to do is make his big, ugly, bad-tempered head.

First we’re going to make his big, ugly head.

All she had was her beloved rat collection.

She only had her beloved rat collection.

Where possible the grammatical structure should be simplified while maintaining the word order.

You can see how metal is recycled if we follow the aluminium.

See how metal is recycled by following the aluminium.

We need energy so our bodies can grow and stay warm.

We need energy to grow and stay warm.

Difficult and complex words in an unfamiliar context should remain on screen for as long as possible. Few other words should be used. For example:

Nurse, we’ll test the reflexes again.

Nurse, we’ll test the reflexes.

Air is displaced as water is poured into the bottle.

The water in the bottle displaces the air.

Care should be taken that simplifying does not change the meaning, particularly when meaning is conveyed by the intonation of words.

Often, the aim of school-programmes is to introduce new vocabulary and to familiarize pupils with complex terminology. When subtitling school-programmes, introduce complex vocabulary in very simple sentences and keep it on screen for as long as possible.

Preferred timing

In general, subtitles for children should follow the speed of speech. However, there may be occasions when matching the speed of speech will lead to subtitle rate that is not appropriate for the age group. The producer/assistant producer should seek advice on the appropriate subtitle timing for a programme.

Avoid variable timing

There will be occasions when you will feel the need to go faster or slower than the standard timings - the same guidelines apply here as with adult timings. You should however avoid inconsistent timings e.g., a two-line subtitle of 6 seconds immediately followed by a two-line subtitle of 8 seconds, assuming equivalent scores for visual context and complexity of subject matter.

Allow more time for visuals

More time should be given when there are visuals that are important for following the plot, or when there is particularly difficult language.

Syntax and vocabulary

Do not simplify sentences, unless the sentence construction is very difficult or sloppy.

Avoid splitting sentences across subtitles. Unless this is unavoidable, keep to complete clauses.

Vocabulary should not be simplified.

There should be no extra spaces inserted before punctuation.

Special Requirements of J/E to CN subtitles for streamers/content creators (Cf. Specific Formatting Rules – Punctuation - Chinese)

(但注意避免连打,如「~~」)

XX酱~

所——以——说

方法一:

糟了 糟了 糟了(实际上念了5个「糟了」)

方法二:

糟了×1

糟了×2

糟了×3

糟了×4

糟了×5

对不起 www

「加油啊XXX」谢谢

(评论:「XXX发狂了」)才没有呢

A:再也不跟你玩了

B:明明约好了要一起玩的啊!

A:骗你的啦

注:FromSoftware,制作了黑魂、只狼、血缘

Comments | NOTHING