Introduction to Relativism (with rough definitions as a first pass)

Relativism comes in miscellaneous forms, but all stripes of relativism agree on at least two features. Firstly, relativism asserts that at least certain properties (like beauty or moral goodness), or classes of things (like knowledge or truth) are not absolute but depend on specific assessment frameworks (such as cultural norms or personal criteria), and the truth of related claims is contingent on identifying the appropriate framework. And secondly, relativists all deny that any framework is uniquely privileged over all others.

(Cf., Baghramian & Carter, 2020; Westacott n.d. -b)

It is also imperative here to underscore the distinction between relativism and expressivism. As contended by Carter (n.d.), relativists adhere to a cognitivist stance, wherein their evaluative judgments principally manifest as expressions of belief rather than some non-cognitive mental states. Relativists do make truth-apt propositions, it is just that their truth or falsity is relative.

The Inception of Relativism (the historical motivation for relativism)

1. Ancient Origins

According to Baghramian (2020) and Westacott (n.d.-a), the concept of relativism, though a contemporary term, finds roots in ancient Western philosophy, notably championed by Protagoras of Abdera around 490–420 BC. Protagoras’s dictum, “Man is the measure of all things,” (Plato, Theaetetus 152a 2–4, as cited in Baghramian & Carter, 2020) serves as an early expression of relativism, suggesting that perception shapes reality. However, the extent of Protagoras’ relativism remains debated, with interpretations ranging from radical subjectivism to a broader ethical dimension. Plato’s rebuttal to Protagoras adds a social and ethical layer to Protagorean relativism, implying that societal or legal norms dictate non-relative truth. His other objection to Protagorean relativism is that it is self-refuting, as it must acknowledge its own falsity if it accepts that those who believe relativism is false are correct.

“…whatever view a city takes on these matters and establishes as its law or convention, is truth and fact for that city.”

Plato, Theaetetus 172a

2. David Hume

Despite its ancient origins, relativism’s implications continue to spark scholarly discussion, reflecting its enduring relevance in philosophical discourse. For example, David Hume (2007a) is famous for his ethical anti-rationalism, which states that moralities are based on sentiment, which is subjective (or relative), rather than on reason, which is rather objective (or non-relative).

“...actions do not derive their merit from a conformity to reason, […] it cannot be the source of moral good and evil, which are found to have that influence. Actions may be laudable or blameable, but they cannot be reasonable or unreasonable…” (p. 240)

“You never can find it, till you turn your reflexion into your own breast, and find a sentiment of disapprobation, which arises in you, towards this action.” (p.244)

David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature (2007a)

Actually, for Hume, even the fundamental operations of our minds, such as the cognition of cause and effect, come from subjective habits or sentiments.

“as this operation of the mind, by which we infer like effects from like causes, and vice versa […] it is not probable, that it could be trusted to the fallacious deductions of our reason” (p. 40)

“Wherein, therefore, consists the difference between such a fiction and belief? […] that the difference between fiction and belief lies in some sentiment or feeling, which is annexed to the latter, not to the former, and which depends not on the will, nor can be commanded at pleasure.” (p. 34)

David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (2007b)

Hume’s anti-rationalist arguments stand close to relativism, however, instead of being a relativist who would assert that such claims are true relative to a particular framework or culture, Hume is rather a sceptic, leading him to doubt whether such claims can ever be justified by reason.

“Yet he has not, by all his experience, acquired any idea or knowledge of the secret power, […] nor is it, by any process of reasoning, he is engaged to draw this inference. But still he finds himself determined to draw it…” (ibid., pp. 31-32)

Therefore, Hume does not endorse the view that multiple, equally valid truths can coexist, as a relativist might; rather, he questions whether we can have any secure knowledge at all.

3. Immanuel Kant

Thereafter, it is Kant, who, being unsatisfied with Hume’s sceptical solution, paved the way for modern relativism in his Critique of Pure Reason by limiting claims of truth to the realm of our phenomenological interactions rather than an independent external reality. Truth judgments, on Kant’s account, are contingent upon our subjective understanding and perception of the world (the Copernican Hypothesis) through transcendental aesthetic and transcendental logic; to posit their truthfulness in the sense of representing an “objective reality” (the noumena) exceeds the boundaries of justifiable human assertion.

“What, then, must be our representation of space, in order that such knowledge of it may be possible? It must in its origin be intuition; for from a mere concept no propositions can be obtained which go beyond the concept - as happens in geometry.”(p. 70, B41)

Kant, Critique of Pure Reason (2007)

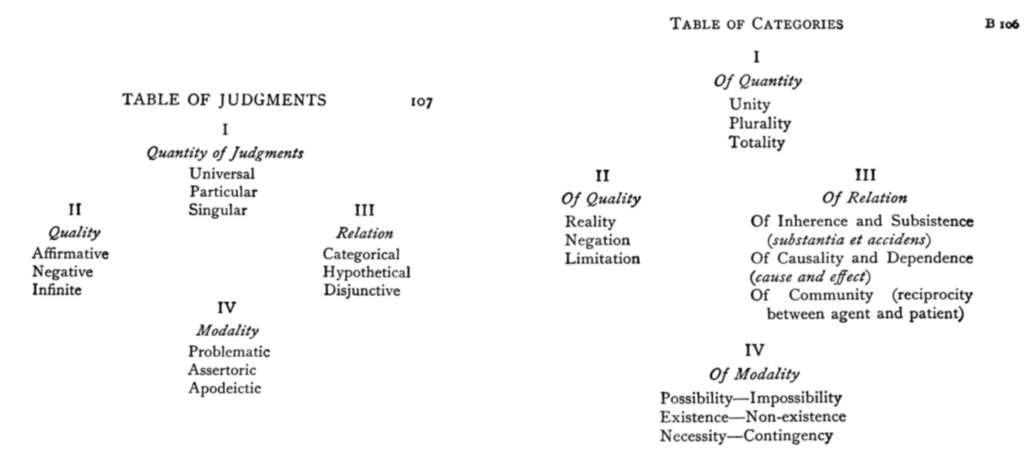

But still, even though Kant “paved the way for modern relativism”, as he deemed truth judgments as “contingent”, he is still not a relativist in light of his “metaphysical deduction”, where he drew a “Table of Judgment” and a “Table of Categories” to underpin a list of basic ways that shows all human beings have a uniformed (or shared) capacity to make sense of “manifolds of intuition” (i.e., the Transcendental Unity of Apperception).

“All the manifold, therefore, so far as it is given in a single empirical intuition, is determined in respect of one of the logical functions of judgment, and is thereby brought into one consciousness. Now the categories are just these functions of judgment, insofar as they are employed in determination of the manifold of a given intuition (cf.§13). Consequently, the manifold in a given intuition is necessarily subject to the categories.” (ibid., p. 160, B143)

“If the understanding as a whole is [thus] nothing but a Vermögen zu urteilen [the capacity to judge], then identifying the totality of functions [...] of the understanding amounts to nothing more and nothing less than identifying the totality of functions present in judging, which in turn are manifest by linguistically explicit forms of judgments.” (Longuenesse, 2006, p. 142)

4. Modern Times

Towards today, it is after the work of philosophers such as Hegel, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Kuhn, Rorty and all those “postmodernists” (roughly, we choose our perspectives), who developed relativism into its “fully-fledged version”.

Epistemological Relativism: A Closer Scrutiny

I shall take the “co-variance definition” here for its brevity, others include the “arity approach” (or the “hidden parameter definition”, according to Baghramian, 2022) and the “negative approach”. The co-variance definition of relativism explores the relationship between a dependent variable, such as values, moralities, or judgments, and an independent variable like cultural paradigms or languages, positing that the former changes in response to variations in the latter. By raising questions about what is relativised and to what it is relativised, this framework distinguishes between various forms of relativism — whether they pertain to truth, ethics, or aesthetics — and their respective domains, such as science or religion. (Cf. Carter 2016, p. 33)

Epistemological relativism, thereby, is what we get when we relativise knowledge claims to epistemic context, such as perspectives, cultures, or other circumstantial factors.

More specifically, within the domain of epistemological relativism, regarding the question of what epistemic context (e.g., “context — including ‘world’ and ‘time’”, “context of use”, or “context of assessment”) is the aforementioned knowledge claims are relativised to, there are two competing approaches: Boghossian’s Replacement Model, and New Semantic Relativism.

Boghossian’s Replacement Model posits a tripartite framework consisting of epistemic non-absolutism, epistemic relationism, and epistemic pluralism.

Epistemic Non-absolutism: Belief justification is not absolute; there are no universal facts about what information justifies a belief.

Epistemic Relationism: To be true, a person’s epistemic judgments must be understood as relative to their accepted epistemic system, C. When they say, “E justifies belief B,” they mean “According to C, E justifies belief B.”

Epistemic Pluralism: There are multiple valid, alternative epistemic systems with no objective basis for determining which is more correct.

New Semantic Relativism challenges the Epistemic Relationism component of Boghossian’s framework, asserting that it inadvertently fosters either Contextualism (when propositions are explicitly relativised to “context”) or Subject-Sensitive-Invariantism (when propositions are explicitly relativised to “context of use”) by making relational assertions necessarily explicit. And according to New Semantic Relativism, these two stances are no better than scepticism. In contrast, New Semantic Relativism posits that cognitive norms should be relativised to the “context of assessment,” enabling the articulation of non-explicitly relational claims while maintaining the relativity of knowledge-claiming propositions.

Traditional Arguments for Epistemological Relativism

1. The Pyrrhonian Problematic

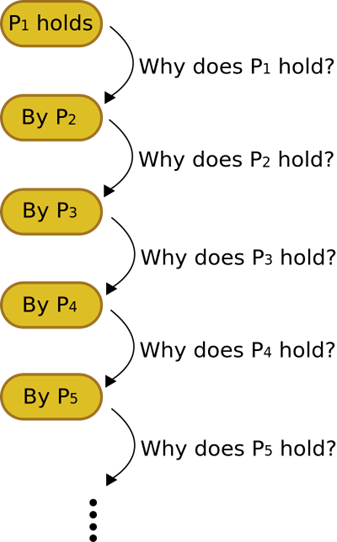

The Pyrrhonian problematic often appears as a foundational argument strategy for epistemological relativism. This puzzle, best exemplified by the infinite regress version, posits that knowledge necessitates an infinite number of justifications, which humans do not possess. Consequently, it appears that all of our beliefs are unjustified. Sceptics thereby challenge their non-sceptical adversaries to refute the assumptions underlying this puzzle.

Sankey (2013)’s relativist argument hereby develops on the Pyrrhonian problematic, consisting of a negative and a positive component. The negative argument, invoking the Pyrrhonian puzzle, concludes that all epistemic norms are equally unjustified. For example, knowledge claim P1 cannot be satisfactorily justified, as either appealing to another claim (P2) results in infinite regress, or appealing to itself (P1) leads to vicious circularity. Applying this reasoning to any other claims (P3, P4, ..., Pn) reveals that all knowledge claims equally lack justification. The positive argument then deduces that epistemic relativism is true, based on the equal standing claim established by the negative argument. As an ultimate grounding for knowledge claims is unattainable, justification must then be based on operative norms within specific contexts. Consequently, beliefs formed in a given context are justified by the norms applicable to that context, while those in different contexts are justified by their respective norms. This allows the relativist to assert that epistemic justification is contingent upon locally operative norms.

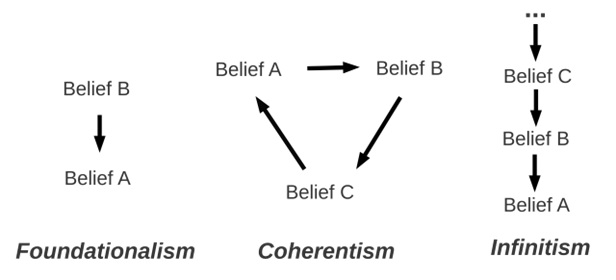

However, Carter (2016) and Seidel (2013) critique Sankey’s argument strategy, questioning its viability for epistemic relativists. Carter argues that the intermediate conclusion — that all norms are equally unjustified — is only valid if foundationalism, coherentism, and infinitism are all deemed unsuccessful. This is a claim that Sankey’s relativist argument does not substantiate.

Consider the following case:

Imagine three scientists debating the cause of a disease:

Scientist A, a foundationalist, argues that a specific virus is the cause of the disease, based on direct, empirical evidence.

Scientist B, a coherentist, suggests that environmental factors are the cause, fitting this idea into a broader, coherent network of scientific understanding.

Scientist C, an infinitist, proposes that the cause is a series of never-ending interactions between the virus and environmental factors, where each interaction leads to another, creating an infinite chain of causes.

A relativist might say that since there’s no definitive way to prove which theory is correct, all three are equally unjustified. However, the critique is that the relativist cannot simply assert equal un-justification without addressing the strengths of each approach. The foundationalist has empirical data, the coherentist has a well-supported theoretical framework, and the infinitist has a nuanced understanding of complex causality. Until the relativist can demonstrate why these approaches fail to justify their theories, the claim of equal un-justification is not substantiated.

Additionally, Seidel (2013) expresses concerns that, even if all epistemic norms are considered equally unjustified, it remains unclear how relativism is preferable to scepticism. Seidel contends that, once all norms are considered equally unjustified, it is uncertain how locally credible epistemic norms can maintain any positive epistemic status, as the relativist desires.

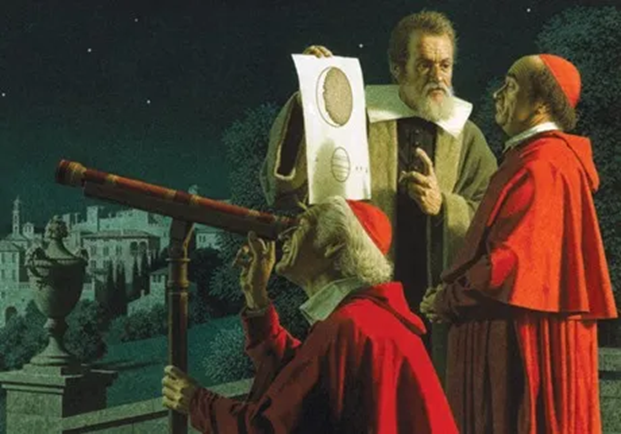

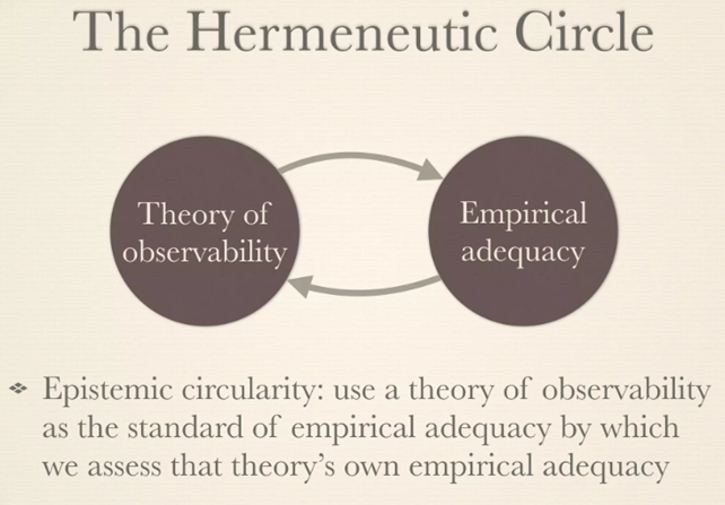

2. Epistemic Circularity

Another argument for epistemic relativism stems from potential epistemic circularity when we are challenged with radically different epistemic systems. For example, Galileo and Cardinal Bellarmine disagreed on the validity of Copernican heliocentrism and the appropriate evidential standards to assess it. Galileo supported the theory with telescopic evidence, while Bellarmine rejected it as heretical, citing scriptures. Attempting to justify our own epistemic system in such situations leads to epistemic circularity, as we inevitably rely on our existing framework for evaluation. This results in the conclusion that all coherent epistemic systems are equally defensible (or indefensible), as they can all be justified through epistemically circular reasoning. This line of thinking involves two key moves: recognizing the inevitability of epistemic circularity when justifying our system and asserting that all systems are equally defensible/indefensible due to this circularity. This, again, allows the relativist to assert that all epistemic systems are contingent upon locally operative norms.

However, contra relativism, an externalist reliabilist might argue that epistemic circularity can be circumvented by asserting that the justification of one’s epistemic framework does not require non-circular proof of its validity. According to this view, if the principles of an epistemic system are reliable, they are justified, even without direct justification of their reliability. By prioritising reliability over justifiability, reliabilism seeks to sidestep the circularity objection. It argues that as long as the processes lead reliably to true beliefs, questioning their justification becomes unnecessary.

Nevertheless, if one chooses the reliabilist approach to avoid epistemic circularity, they may still inadvertently encounter another form of circularity known as bootstrapping. This occurs when an individual uses their own epistemic principles to gather evidence of their reliability.

“One would be in a position to acquire track-record evidence via the deliverances of applying one’s own epistemic principles that the application of one’s own epistemic principles is reliable.”

Westacott, n.d.

Consider the following case:

Imagine a person named Alex, who has always relied on his intuition to make important life decisions, such as choosing a career, selecting friends, or deciding where to live. Alex’s intuition has served him well in the past, leading to generally positive outcomes. As a result, Alex believes that his intuition is a reliable source of knowledge and decision-making.

Now, consider a situation where Alex faces a new decision, such as whether to invest in a particular business opportunity. Alex’s intuition tells him that the investment is a good idea. To justify this belief, Alex reflects on his past experiences and the successful decisions he have made using his intuition. He concludes that because his intuition has been reliable in the past, it must be reliable now.

In this example, Alex is engaging in bootstrapping. He is using the track record of his intuition (derived from applying his own epistemic principles) to gather evidence that his intuition is reliable. However, this reasoning is circular, as the evidence for the reliability of his intuition is based on the very intuition he is trying to justify. The bootstrapping problem arises because Alex’s justification for trusting his intuition is not independent of the intuition itself, leading to a potentially unreliable belief system.

3. An End?

The bootstrapping problem to the reliabilist account hereby seems to put relativism back in favour. But debates went on…

The problem is, even assuming that the epistemically circular justification for one’s own epistemic principles (and, more broadly, one’s epistemic system) results in all epistemic principles being on an equal footing, this equal-footing scenario is consistent with both scepticism (that all epistemic systems are unjustified) and relativism (that epistemic systems are relative). To effectively argue for epistemic relativism from this position, one must provide a non-arbitrary rationale for choosing relativism over scepticism. And Relativism, under Boghossian’s Model, have troubles meeting this challenge.

Arguments for New Semantic Relativism

Hitherto, we could see that a common criticism to traditional arguments for epistemic relativism (regarding the preceding Pyrrhonian case and the alien epistemic system case, at least) is that they struggle to demonstrate why, considering the philosophical issues discussed, relativism is a better choice than scepticism. Relativism, on Boghossian’s account, seems incapable of dealing with this problem. This is the problem that New Semantic Relativism deals with.

To understand New Semantic Relativism, consider MacFarlane (2014)’s Conundrum as follows:

“If you ask me whether I know that I have two dollars in my pocket, I will say that I do. I remember getting two dollar bills this morning as change for my breakfast; I would have stuffed them into my pocket, and I haven’t bought anything else since. On the other hand, if you ask me whether I know that my pockets have not been picked in the last few hours, I will say that I do not. Pickpockets are stealthy; one doesn’t always notice them. But how can I know that I have two dollars in my pocket if I don’t know that my pockets haven’t been picked? After all, if my pockets were picked, then I don’t have two dollars in my pocket. It is tempting to concede that I don’t know that I have two dollars in my pocket. And this capitulation seems harmless enough. All I have to do to gain the knowledge I thought I had is check my pockets. But we can play the same game again. I see the bills I received this morning. They are right there in my pocket. But can I rule out the possibility that they are counterfeits? Surely not. I don’t have the special skills that are needed to tell counterfeit from genuine bills. How, then, can I know that I have two dollars in my pocket? After all, if the bills are counterfeit, then I don’t have two dollars in my pocket.”

How to explain our different knowledge attributions under different circumstances, then? (The invariantist’s dilemma)

As elaborated in the preceding section, the Boghossian interpretation of Relativism, by its entailment of epistemic relationism, leads to either Contextualism or Subject-Sensitive-Invarianism.

In subsequent sections, I shall provide an exposition on how contextualism and Subject-Sensitive-Invarianism address the invariantist’s dilemma, and demonstrate that their solutions do not fully solve the issue, leaving them no better than scepticism. Furthermore, I will present that the resolution offered by New Semantic Relativism to this dilemma appears, at least prima facie, to be satisfactory, rendering it a more favourable position than scepticism.

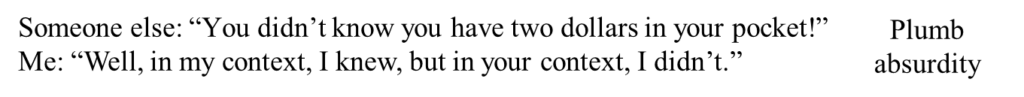

In answering MacFarlane’s Conundrum, Contextualism explains the variability in our knowledge attributions by suggesting that the meaning of “knows” depends on the context, requiring the ruling out of contextually relevant alternatives (e.g., pickpockets and counterfeits). This approach avoids the invariantist’s dilemma, however, treating “knows” like a context-dependent term such as “tall” introduces new issues. When people disagree about knowledge, it’s not as simple as clarifying what they mean by “tall” in different situations. If someone challenges your claim that you know you have two dollars, you can’t just say, “Well, in my context, I knew, but in your context, I didn’t.” People expect a real defence or retraction of the claim, not a statement that both are true in their own ways. This makes our everyday knowledge claims no better than scepticism if we accept contextualism.

Subject-Sensitive-Invariantism (SSI), suggests that the truth of a knowledge claim, like “I know I have two dollars in my pocket,” depends on the practical stakes involved for the subject, I, rather than the broader context where the subject is in. It considers whether the subject has the ability to rule out relevant alternatives based on the subject’s practical stakes, which differs from contextualism’s broader focus on the context where the subject finds himself in. SSI has advantages, such as explaining disagreement and variability in knowledge attributions without treating “knows” like “tall.”

E.g., Someone else: “You didn’t know you have two dollars in your pocket! Because you didn’t have the ability of recognising counterfeit money”

Me: “While it’s true that I did not possess the capability to identify counterfeit money, this does not necessarily invalidate my knowledge claim that ‘I know I have two dollars in my pocket.’ Subject-Sensitive Invariantism posits that the truth conditions of a knowledge claim are sensitive to the practical stakes involved for me, the knowing subject. In this case, the practical stake was whether the two dollars in my pocket were genuine or not. If the importance of this distinction was low in my practical situation—say, if I did not intend to use the money in a context where its authenticity would be challenged—then my inability to recognize counterfeit money would not undercut my knowledge claim. My knowledge is evaluated based on whether the ability to discern counterfeit bills was relevant and necessary in my practical circumstances, not merely on the abstract ability itself.”

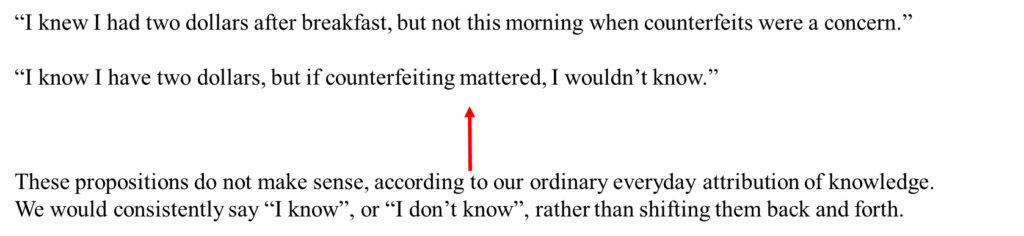

However, SSI faces challenges with temporal and modal embeddings of knowledge claims. Critics argue that SSI predicts knowledge attributions should change based on the subject’s practical environment in shifted circumstances, but people tend to evaluate the relevance of alternatives consistently across non-embedded and embedded uses of “know.” For example, one might not say, “I knew I had two dollars after breakfast, but not this morning when counterfeits were a concern,” or “I know I have two dollars, but if counterfeiting mattered, I wouldn’t know.” These propositions do not make sense, according to our ordinary everyday attribution of knowledge. We would consistently say “I know”, or “I don’t know”, rather than shifting them back and forth.

The conclusion is that while each of the two theories — contextualism and Subject-Sensitive-Invarianism — has strengths, none fully captures our willingness to attribute knowledge without a significant drawback. This is the motivation of MacFarlane in proposing New Semantic Relativism.

Therefore, MacFarlane proposes a relativist semantics for knowledge attributions that meets three key requirements:

Alternative-variation: The view must explain how the relevant alternatives for knowledge vary with context, avoiding the invariantist’s dilemma.

Alternative variation with the context of use (e.g., intentionality of the interlocutors): The alternatives must not vary with the context of use, preserving disagreement as contextualism fails to do.

Alternative variation with practical stakes of the subject: The alternatives must not vary with the subject’s practical stakes, addressing the temporal and modal embedding issues of SSI.

Under these three requirements, MacFarlane argued that our cognitive norms shall be relativised to context of assessment. This means that statements like “I knew I have two dollars in my pocket this morning” can be true in one context of assessment (e.g., the context where counterfeit possibilities are not taken into the assessment considerations) and false in another context of assessment (e.g., the context where counterfeit possibilities are taken into the assessment considerations), regardless of whether the context or subject’s practical stakes include discerning the counterfeit possibility or not.

Essentially, if the context of use or the speaker’s practical stakes change over time (for example, whether the subject has heard “the counterfeit story” or not), the statement’s truth isn’t automatically altered. What’s crucial is whether the context of assessment takes into account the potential for the money to be counterfeit or not. Concisely, New Semantic Relativism provides a middle ground between the extremes of scepticism and traditional relativism. It acknowledges the role of context in shaping what is considered relevant for assessing truth, without reducing truth to mere perspective or framework, making it preferable than both traditional relativism and scepticism.

Summer, 2024

References

Baghramian, M., & Carter, J. A. (2020, September 15). Relativism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Retrieved May 12, 2024, from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/relativism/

Boghossian, P. (2006). Fear of knowledge: Against relativism and constructivism. Clarendon Press.

Carter, J. A. (n.d.). Epistemology and Relativism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved May 12, 2024, from https://iep.utm.edu/epis-rel/

Carter, J. A. (2016). Global relativism. In Metaepistemology and Relativism (pp. 31–58). Palgrave Macmillan.

Hume, D. (2007a). A treatise of human nature (D. F. Norton & M. J. Norton, Eds.).

Hume, D. (2007b). An enquiry concerning human understanding (P. Millican, Ed.). Oxford University Press.

Kant, I. (2007). Critique of Pure Reason (N. K. Smith, Trans.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Longuenesse, B. (2006). Kant on a priori concepts: the metaphysical deduction of the categories. In The Cambridge Companion to Kant and Modern Philosophy (pp. 129–168).

MacFarlane, J. G. (2014). Assessment sensitivity: Relative Truth and Its Applications. Oxford University Press.

Sankey, H. (2012). Scepticism, relativism and the argument from the criterion. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science. Part a/Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 43(1), 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2011.12.026

Seidel, M. (2013). Scylla and Charybdis of the epistemic relativist: Why the epistemic relativist still cannot use the sceptic’s strategy. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science. Part a/Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 44(1), 145–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2012.10.004

Vogel, J. (2000). Reliabilism leveled. The Journal of Philosophy, 97(11), 602. https://doi.org/10.2307/2678454

Westacott, E. (n.d.-a). Cognitive Relativism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved May 12, 2024, from https://iep.utm.edu/cognitive-relativism-truth/

Westacott, E. (n.d.-b). Relativism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved May 12, 2024, from https://iep.utm.edu/relativi/

Comments | NOTHING